|

|

|

|

The Pianist by Wladyslaw Szpilman

on stage

France/England/Germany - press

Présentation

En 1939, Radio Pologne est réduite au silence à l'instant où Wladyslaw Szpilman interprète en direct le 'Nocturne no 1' de Chopin.

Varsovie devient un véritable piège où, au rythme des rafles des Juifs, Szpilman réussit pourtant à subsister alors que tous ses proches sont conduits aux camps de la mort. Pendant deux ans, il va vivre une longue période d'incertitude durant laquelle il erre, se cachant des Allemands. Il déclarera par la suite : l'isolement absolu était la condition de ma survie. Et la musique...

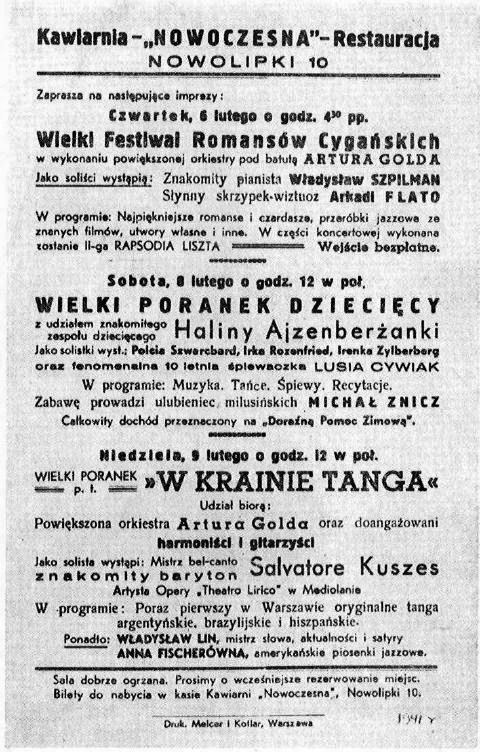

Avant le célèbre film de Polanski, Robin Renucci avait adapté pour la scène le livre de Szpilman..

Le Pianiste.

De Wladyslaw Szpilman

Adaptation de Robin Renucci

Musique de Frédéric Chopin, Wladyslaw Szpilman

Mise en scène Cécile Guillemot

Avec Robin Renucci

Et les pianistes Mikhaïl Rudy, Nicolas Stavy

Théâtre

Le pianiste, à Monaco

par Elsa Menanteau, samedi 1er août 2009

Le comédien Robin Renucci et le musicien Mikhaïl Rudy font redécouvir l’histoire du pianiste polonais Wladyslaw Szpilman, dont l’histoire, véridique, a été portée à l’écran par Roman Polanski. Au fort Antoine, à Monaco.

Le lundi 3 août , l’acteur Robin Renucci et le pianiste Mikhaïl Rudy inviteront le public à découvrir ou re découvrir , le destin incroyable du pianiste polonais Wladyslaw Szpilman.

L’histoire vraie qui sera contée est celle de la survie d’un être humain capable de puiser dans des situations extrêmes, au plus profond de lui même, des ressources phénoménales. Le conte de l’auteur est ponctué par la musique romantique de Chopin. Deux mondes, en somme, qui s’interposent, puis se complètent et enfin s’unissent. Cette union fut d’ailleurs capitale pour Szpilman, qui n’aurait pas survécu sans cette musique,son art lui sauva la vie.

Le livre de Szpilman, Le pianiste a été porté à l’écran par Roman Polanski avec le succès que l’on connaît.

Ne manquez pas Le Pianiste!

le 26.02.07 - www.lemondedelamusique.com

Vous avez aimé le film de Roman Polanski Le Pianiste ? Vous avez dévoré dans la foulée le magnifique récit de Wladyslaw Szpilman qui l’a inspiré (Editions Robert Laffont) ? Courez alors aux Bouffes du Nord, où le comédien Robin Renucci et le pianiste Mikhaïl Rudy reprennent la version scénique de cette histoire exemplaire, qu’ils ont fait triompher en 2005 à travers toute la France. Le cadre magnifique et décati, le grand espace peuplé d’ombres du théâtre de Peter Brook ajoute à l’étrangeté de cet échange virtuose de mots et de musique, à ce numéro de haute école consistant à frôler la sensiblerie sans jamais y tomber.

Le Pianiste, de Wladyslaw Szpilman, musique de Frédéric Chopin, Wladyslaw Szpilman. Mise en scène de Cécile Guillemot. Avec Robin Renucci et Mikhaïl Rudy (Nicolas Stavy du 13 au 17 mars).

Théâtre des Bouffes du Nord

37 bis boulevard de la Chapelle, 75010 Paris, jusqu’au 17 mars. Tous les soirs à 21h, sauf dimanche et lundi, matinée samedi à 15h30. www.bouffesdunord.com

Sobriété et dépouillement étaient au rendez vous de ce pianiste incarné par Robin Renucci et son double, Mikhaïl Rudy, l'un récite les lettres écrites par Wladyslaw Szpilman, l'autre joue Chopin, pour raconter l'histoire de la survie de ce pianiste caché en plein ghetto de Varsovie et adapté à l'écran en 2002 par Roman Polanski.

Sobriété du jeu de cet acteur qui porte la pièce pour l'avoir écrite, interprétée et dépouillement du décor dans ce théâtre des Bouffes du Nord où l'état de délabrement permet de se passer d'autres décors. Sobriété également des lumières qui nous proposent des ombres.

Un récit lent, descriptif sans être mélodramatique et une force d'évocation.

du 21 février au 17 mars 2007 au théâtre des Bouffes du Nord, 37 bis boulevard de la Chapelle, 75010 Paris

« Quand j’entends le mot culture, je sors mon revolver. » Cette sentence sort de la bouche d’un SS. Robin Renucci la rappelle volontiers à nos mémoires. L’utilise comme un signal d’alarme. « ne pas sous estimer le pouvoir de la culture dans une société où les valeurs démocratiques vont à vau l’eau. »

Le comédien militant s’est donc emparé du texte « Le Pianiste », de Wladyslaw Szpilman, qu’il joue depuis mardi au théâtre Pépinière-Opéra. Ce récit d’un musicien virtuose, juif de Varsovie, terré pour survivre à la Shoah, bouleversait déjà le grand public en 2002 dans le film de Roman Polanski, palme d’or à Cannes. Le roman venait tout juste d’être consacré « meilleur livre de l’année » par le magazine Lire en 2001. Robin Renucci, lui, découvre le texte avant sa parution et sa version cinématographique, lors d’une lecture à la maison du Judaïsme en 1998. Bouleversé, il décide alors de l’adapter à la scène au Festival des Estivales de Perpignan, au côté du célèbre concertiste Mikhaïl Rudy. Résultat : un spectacle où les notes ont autant d’importance que les mots.

On comprend l’engouement de Renucci pour le témoignage de Szpilman, publié en Pologne en 1946, mais immédiatement retiré des vitrines par le régime communiste. Il raconte comment l’homme devait être déporté en 1942 avec sa famille. Un policier, ébloui par les talents musicaux, lui sauve la vie une première fois. Libre, Szpilman est contraint de se cacher pendant deux ans et demi, jusqu’à la liquidation du ghetto de Varsovie et la destruction de la ville. On le retrouve gelé, agonisant, en réclusion morale et physique. Il sera sauvé une deuxième fois par un officier allemand, Wilm Hosenfeld, hanté par les crimes commis par son peuple. On nommera dès lors Szpilman « Le Robinson Crusoé » de Varsovie.

« Qu’est-ce qui fait qu’un homme est épargné plus qu’un autre ? souligne Renucci. Quelle résistance à la vie lui permet de repousser à ce point les limites de l’endurance ? Est-ce sa foi en l’humain et en la musique ? Sa conscience d’un travail à porter haut et à mener loin ? » Une mission change peut-être un destin. Mais être sauvé par un talent n’est pas gage de sérénité : « L’homme vivra dans la culpabilité d’être le vivant parmi les morts » poursuit Renucci. D’être « celui qui a sauvé sa peau ». Il n’aura pas la chance de voir son livre s’arracher, d’avoir entendu. Il consacrera sa vie à la musique. Pour respecter la force de cette parole donnée, Robin Renucci a opté pour l’exigence. Un spectacle qui propose juste des extraits du texte : « Je respecte le film de Polanski. Mais je reste convaincu que l’on ne doit pas traiter de cette période sur le mode de la fiction. Au cinéma comme ailleurs. Trop de non dits persistent : par exemple, au sortir de la seconde guerre mondiale, on parlait de millions de morts, au sujet de la Shoah, sans préciser que c’était des juifs. Et on entendait encore dans la bouche des Allemands : « On ne savait pas ». Il faut être à l’affût. Aujourd’hui encore, il y a encore des génocides, au Soudan ou au Tchad. Il faut traiter de ces sujets au plus près, avec vérité, c’est une question de respect, de conscience. »

La transmission, c’est le truc de Robin Renucci. Ses grands rôles au théâtre, au cinéma et à la télévision ne l’ont pas empêché à défendre un art engagé. De s’ouvrir à une « transversalité des arts », qui mêle ingénieusement théâtre, musique et connaissance du monde. Il s’y applique au cœur de l’Aria (association des rencontres internationales artistiques, pôle d’éducation et de formation créé en 1998), organisatrice d’un festival juillettiste et corse très reconnu. Devant la cohérence et l’investissement de Robin Renucci, devant l’étendue de ses talents et la qualité de ses choix artistiques, on serait volontiers béat d’admiration.

Delphine de Malherbe

Hasard de la programmation théâtrale, c'est quelques jours après le 60e anniversaire de la libération d'Auschwitz que Robin Renucci fait revivre, au Théâtre de la Pépinière-Opéra, le héros du « Pianiste », rendu célèbre par le film de Roman Polanski, Palme d'or à Cannes en 2002, récompensé par trois Oscars à Hollywood en 2003. Le comédien a adapté pour la scène le livre de Wladyslaw Szpilman, ce musicien juif polonais qui vécut deux ans et demi caché dans le ghetto de Varsovie pour échapper à la déportation. Robin Renucci a choisi de mettre en musique son récit, accompagné au piano par le concertiste russe Mikhaïl Rudy (en alternance avec Nicolas Stavy), qui interprétera des oeuvres de Chopin et de Szpilman lui-même, dans une mise en scène très dépouillée de Cécile Guillemot.

La musique « témoigne que du pire peut surgir le meilleur »

« J'avais fait une lecture à partir de son récit il y a quatre ou cinq ans, à la Maison du judaïsme et, depuis, je portais ce texte en moi, raconte Robin Renucci. J'en avais parlé à Roman Polanski, lors d'une rencontre à Bucarest. Il avait acheté les droits d'exploitation pour le cinéma, moi pour le théâtre. J'ai vu le film de Roman, et j'ai compris très vite que la présence de la musique était essentielle pour l'adaptation sur scène. Elle témoigne que du pire peut surgir le meilleur, que du chaos peut naître la création artistique. » Le bouleversant récit de Renucci raconte la survie dans le ghetto de celui qu'on avait surnommé après-guerre « le Robinson Crusoé de Varsovie », son désespoir, sa solitude, son évasion via la musique qu'il compose dans sa tête. Il évoque aussi la noirceur du contexte de l'époque, les rafles de Juifs, le départ des trains vers les camps de concentration. Et puis, l'espoir qui survient là où on ne l'attend plus. « Je me suis attaché à mettre en valeur la rencontre entre le pianiste et cet officier allemand hanté par l'atrocité des crimes de son peuple, à qui il devra finalement sa survie », précise le comédien. Fondateur des Rencontres internationales théâtrales de Corse, auxquelles collaborent chaque été habitants de l'île de Beauté et comédiens professionnels, Robin Renucci conçoit son travail comme celui d'un « passeur, un relais entre un auteur et le public ».

Sa démarche s'accompagne d'une exigence de textes forts. On l'a vu au théâtre dans « Bérénice » mis en scène par Lambert Wilson, dans « le Grand Retour de Boris S. » monté par Marcel Bluwal. « Je refuse beaucoup de choses, quitte à paraître sectaire, reconnaît-il. La nécessité de monter le Pianiste s'est imposée à moi. Il y a un tel souffle, une telle émotion dans ce récit et cette musique qu'on sort de là touché, grandi. C'est une belle réponse à l'amnésie qui frappe la société actuelle, à cette pensée négationniste qui continue de se répandre insidieusement.»

Hubert Lizé

Un spectacle, c’est toujours un peu un aveu. Une confidence. Ce Pianiste proposé par Robin Renucci et Mikhaïl Rudy et placé dans la lumière de l’entente profonde des deux interprètes nous révèle quelque chose qui dépasse le propos même qu’il entend cerner. On est au-delà d’une histoire, dans l’histoire.

Cette adaptation du récit de Wladyslaw Szpilman que le beau film de Roman Polawski a contribué à rendre proche de nous est d’une sobriété plus puissante, plus forte que ne le serait un facile appel à l’émotion. Par-delà le destin paradoxal de Wladyslaw Szpilman, c’est à la fatalité de vivre que nous sommes renvoyés insensiblement.

Wladyslaw Szpilman, pianiste et compositeur, juif polonais dont on entend sur les ondes de la radio nationale en septembre 1939 du Nocturne en Ut dièse mineur de Chopin, va échapper à la déportation, se cacher, être sauvé une fois encore. Sombre destin qu’il racontera en 1946 dans un livre extrêmement sobre mais que les autorités communistes firent tout pour étouffer. Et lui, se sentant coupable, fera tout sans doute obscurément, pour effacer, s’effacer.

Sur le plateau, ils sont deux, dans les lumières douces de Julien Barbarin, et dans la lumière renvoyée par le grand piano, protagoniste essentiel de cette célébration fervente. Deux comme deux frères, tout de noir vêtus. Concentrés et graves. Se répondant, quoi de plus simple ? Pages du livre traduit par Bernard Cohen, pages de musique. Chopin et Szpilman. Dialogue. Le sens, ici, vient autant de la musique que des mots. Mais elle n’est jamais paraphrase. Extraordinaire présence du grand virtuose qu’est Mikhaïl Rudy ici dans la fraternité du théâtre. Robin Renucci, maître de la moindre de ses inflexions, mais dans la rigueur – jamais il ne va chercher l’émotion, tout est retenu. Question de doigté d’une délicatesse éblouissante. Jamais de démonstration. Le récit dans sa sincère simplicité et la musique dans ses subtiles nuances. Du théâtre, de la musique. Une spiritualité qui flambe haut. Comme une prière en laquelle chacun, d’où qu’il vienne, se reconnaît au plus profond.

Armelle Héliot

Un homme qui lutte pour sa survie avec le secours de Chopin...

C'est un miracle de sobriété, de rigueur, de fidélité et d'émotion ! Vêtu de sombre, très concentré, Renucci parle simplement, sans chercher l'effet. Mais dans sa bouche, le texte sonne vrai, prend du relief, éveille des images et nous touche par son authenticité, d'autant que Mikhail Rudy, sur son Steinway de concert, l'illustre en virtuose. Magnifique ! Les notes et les mots se relaient ainsi, porteurs chacun de charge émotionnelle. On pouvait craindre des excès dans l'expression des sentiments et un certain manichéisme dans les jugements. Il n'en est rien. Il y a, ici, quelques bons Allemands et quelques mauvais Juifs. Il y a surtout un homme qui lutte pour sa survie en proie à la peur et à la faim. Avec le secours de Chopin...

André Lafargue

Théâtre contemporain

Du 02/02/05 au 15/05/05

LE PIANISTE

LA PEPINIERE-OPERA THEATRE MUSICAL

7, rue Louis-le-Grand

75002 PARIS

A savoir

de Wladyslaw Szpilman. Avec Robin Renucci, Mikhaïl Rudy et en alternance avec Nicolas Stavy. Musique Frédéric Chopin et Wladyslaw Szpilman.

Dans le Ghetto de Varsovie pendant la guerre, l'extraordinaire destin d'un musicien juif qui doit sa survie à un policier mélomane hanté par l'atrocité des crimes nazis. Après le livre de Szpilman et le film de Polanski, ce récit bouleversant est porté à la scène par un grand comédien et un pianiste virtuose.

Le Figaro 15 Fevrier 2005:

Palais des Festivals et des Congres Cannes

30es Nuits Musicales du Suquet

Parvis Notre-Dame d’Espérance lundi 18/07/2005

21h15

Pianiste de Wladyslaw Szpilman

avec Robin Renucci, Mikhaïl Rudy

Frédéric Chopin : Nocturne op.27, n°2 en ré bémol majeur

Wladyslaw Szpilman : Concertino, extraits

Frédéric Chopin : Mazurka op.63, n°3 en do dièse mineur

Prélude op.28, n° 4 en mi mineur

Prélude op.28, n°15 en ré bémol majeur

Prélude op.28, n°20 en do mineur

Sonate en si bémol mineur, 1er mouvement

Wladyslaw Szpilman : Suite pour piano, extraits

Frédéric Chopin : Nocturne en do dièse mineur, op.27, n°1

Nocturne op.48, n°1 en do mineur

Prélude op.28, n°7

Prélude en ré bémol majeur, op.27, n°2

• Un pianiste dans le ghetto de Varsovie

Bouleversé par le livre de Wladislaw Szpilman dont Roman Polanski a fait un film, Robin Renucci a eu le désir de l’adapter au théâtre en faisant une large place à la musique de Chopin dont “le pianiste” était un grand interprète. Ce spectacle met en scène deux grands artistes, le pianiste Mikhail Rudy et le comédien Robin Renucci qui nous en offrent une version où la charge émotionnelle, la force des mots et les envolées musicales résonnent, incarnant la dimension tragique du destin de ce Juif polonais désormais immortalisé…

« J’ai été bouleversé par cette histoire vraie de ce jeune pianiste virtuose piégé dans le ghetto de Varsovie, que le destin a repêché à plusieurs reprises et que la musique a sauvé. (…) Je me suis fait un devoir de reprendre avec précision les mots de Szpilman. Pour moi, ce qui compte, ce sont les mots justes et la musique. Rien d’autre. J’ai adapté son livre, mais en étant au plus près de son texte. Et j’ai demandé à Mikhaïl Rudy de jouer du piano parce que Szpilman vivait et a survécu grâce à la musique, grâce aux partitions qu’il se repassait dans sa tête. » Robin Renucci in France Soir, 2005

Traduction française de Bernard Cohen.

Musique de Frédéric Chopin et Wladyslaw Szpilman. La conception musicale et le choix des oeuvres de ce spectacle sont de Mikhaïl Rudy.

• Les mots justes et la musique

Dès sa sortie, Robin Renucci a été bouleversé par le livre Le pianiste de Wladislaw Szpilman, dont très vite il a fait les lectures à la Maison du Judaïsme. Robin a eu envie de monter un vrai spectacle qui donnerait une large place à la musique, principalement celle de Chopin dont Wladislaw Szpilman était un grand interprète, et dont le nocturne en do dièse mineur joue un rôle clé dans le déroulement de l’histoire du livre.

C’est de cette idée qu’est née la rencontre de Mikhail Rudy et de Robin Renucci sur l’initiative du Festival des Estivales de Perpignan où Le pianiste a été créé en 2002. Les deux artistes ont travaillé ensemble pour élaborer deux heures de spectacle (environ une heure de musique et une heure de textes entremêlés) où la musique de Chopin prolonge les émotions du texte. Le spectacle a été donné devant une salle comble du Palais des Rois de Majorque et a reçu un accueil enthousiaste.

Le fils de Wladislaw Szpilman, qui est à l’origine de la sortie du livre, a assisté au spectacle dont il a été tellement satisfait qu’il a demandé à Mikhaïl Rudy de faire la création en Pologne des œuvres pour piano composées par son père. Mikhaïl Rudy a ainsi interprété le Concertino pour piano et orchestre écrit dans le ghetto et évoqué dans le livre et la Suite pour piano miraculeusement redécouverte récemment. Le concert a eu lieu à la Philarmonie de Varsovie à l’occasion de la Première du film de Roman Polanski, lors d’une soirée très émouvante réunissant les membres de la famille Szpilman et largement relayée par la presse polonaise.

• La presse

« Du théâtre, de la musique. Une spiritualité qui flambe haut. Comme une prière en laquelle chacun, d’où qu’il vienne, se reconnaît au plus profond. » Armelle Héliot,

Le Figaro, février 2005

« Sans rien montrer, par la seule force de l’évocation. On est ému, bouleversé par le récit pudique et grave. C’est remarquable. » Annie Chénieux, La Journal du Dimanche, février

2005 PARISCOPE

Avant que le tonnerre d’applaudissement n’éclate dans la salle, un silence chargé d’émotion se fait entendre. Et c’est beau. LE FIGARO

C’est plus que du charme. C’est une façon généreuse d’être au monde. Une sincérité. Une présence pleine. De ses premières apparitions sur les tréteaux, il y a 25 ans, en passant par une carrière sans défaut au cinéma, Robin Renucci n’a guère changé. Il a mûri. C’est un fougueux, un ardent. Il possède l’esprit des bâtisseurs. Sa vie c’est entreprendre, transmettre donner.

LE JOURNAL DU DIMANCHE

Devant la cohérence et l’investissement de Robin Renucci, devant l’étendue de ses talents et la qualité de ses choix artistiques, on serait volontiers béat d’admiration. [ ... ] On est ému, bouleversé par le récit pudique et grave. C’est remarquable.

LE PARISIEN

itw Robin Renucci « La nécessité de monter Le Pianiste s’est imposé à moi. Il y a un tel souffle, une telle émotion dans ce récit et cette musique qu’on sort de là touché, grandi. C’est une belle réponse à l’amnésie qui frappe la société actuelle, à cette pensée négationniste qui continue de se répandre insidieusement. »

FRANCE SOIR

itw Robin Renucci « Je me suis fait un devoir de reprendre avec précision les mots de Szpilman. Pour moi, ce qui compte, ce sont les mots justes et la musique. Rien d’autre. »

LE FIGARO

Le récit dans sa sincère simplicité et la musique dans ses subtiles nuances. Une spiritualité qui flambe haut.

LES ECHOS

Robin Renucci a réussi l’impossible : faire du Pianiste, récit autobiographique de Wladyslaw Szpilman, un spectacle de théâtre. [ ... ] Robin Renucci évoque avec une retenue exemplaire, d’une voix presque blanche et pourtant toujours

nette, ces moments de souffrance, de courage et d’horreur. [ ... ] Deux hommes en noir sur une scène minuscule : l’un des plus beaux spectacles de l’hiver

LE PARISIEN

C’est un miracle de sobriété, de rigueur, de fidélité et d’émotion ! Le texte sonne vrai, prend du relief, éveille

des images et nous touche par son authenticité, d’autant que Mikhail Rudy, sur son Steinway de concert, l’illustre en virtuose

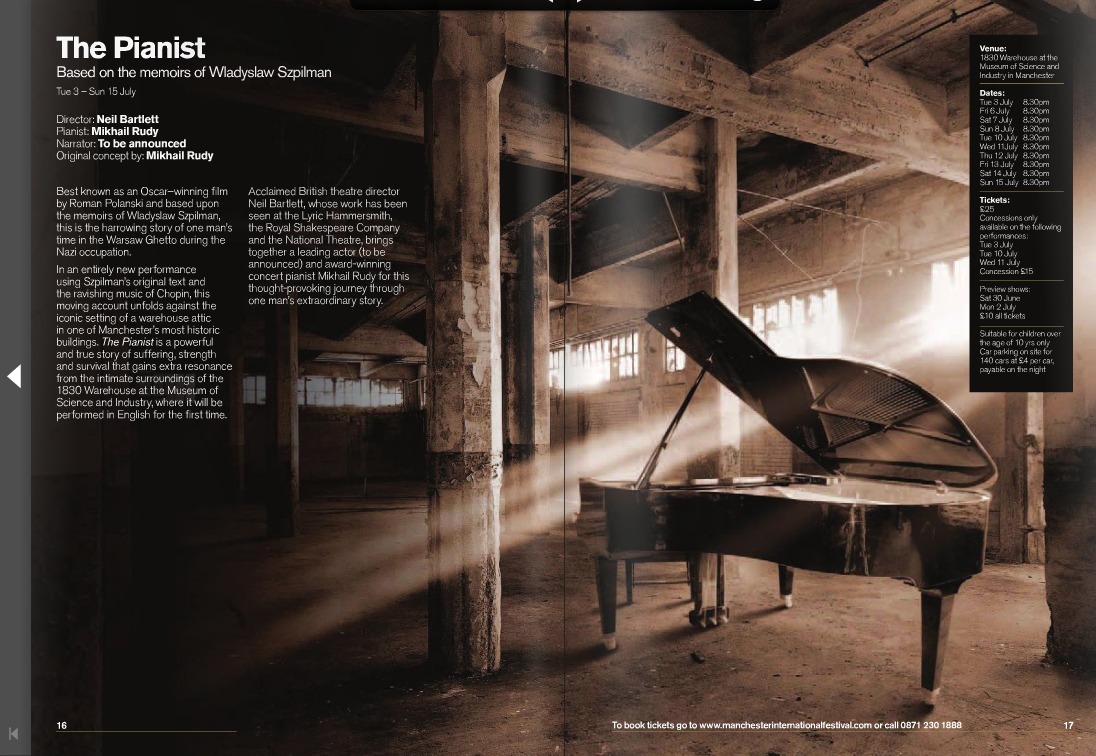

The Pianist

Book by Wladyslaw Szpilman

Manchester International Festival

1830 Warehouse at the Museum of Science and Industry, Manchester

Review by David Chadderton (2007)

An actor telling stories to an audience accompanied by a musician in an attic room of an old warehouse sounds like a typical Edinburgh Fringe small-scale show. However when the team consists of well-known actor Peter Guinness, concert pianist and artistic director of the Festival de St Riquier in France Mikhail Rudy and former artistic director of the Lyric Hammersmith Neil Bartlett with a text from the same source as an acclaimed film by Roman Polanski, it becomes something that tempts the first-string critics of the national dailies out of London to the rainy north.

The experience of this production begins long before entering the performance space. The car park is an old cobbled street (sadly not at wartime prices, but £4 isn't unreasonable for the centre of Manchester) from where you walk across the old railway tracks and sit in the bar, which is the old partially-covered station platform, listening to loud, ghostly recorded sounds of steam trains. The audience is then led across a footbridge over the railway tracks through a loading door into a haze-filled room with bright lights and dark corners, up some stairs (there is also a lift) and into a small, square room with wooden floor, walls, ceiling and beams, seats on all four sides and a grand piano in the centre.

The text consists of extracts from the wartime memoirs of Wladyslaw Szpilman, who worked as a pianist for Warsaw radio until the Nazi occupation, spoken in the rich but melancholy tones of actor Peter Guinness. Szpilman saw his city turned into a ghetto and his family taken away on trains, never to return, but he somehow managed to survive in hiding in the city until it was liberated by the Russians in 1945. Punctuating the performance at regular intervals are pieces of music written by Chopin and by Szpilman himself, played by Mikhail Rudy who created the idea for the show and whose own family was constantly on the move when he was a child to escape persecution by Stalin. The music is not intended to provide any narrative, but it often does capture and heighten the mood of the text.

The different elements do come together successfully into a very interesting piece of theatre. There are some beautifully-described if quite harrowing scenes from Szpilman's life, but it does feel as though the story has some great big gaps in it as the pieces of text are chosen more for their individual effect than their part in the plot, which makes it difficult to get a sense of overall timescale or to really understand the intensity of the suffering he must have had to endure.

The piece is lit simply but cleverly by Chris Davey, allowing Guinness to appear to wander freely around the room but to still be lit quite tightly at times. Matt Wand's sound design very subtly amplifies Guinness's voice and touches in the occasional barely-audible wind sound for dramatic effect.

On the face of it, this is very similar to many other wartime stories of Nazi atrocities against the Jews and Eastern Europeans, but it is told in an engaging and fairly original way here. The music, even though some pieces are long, helps to break up the harrowing tales without destroying the mood. Overall, this is a fascinating piece of theatre that is extremely well performed by both the actor and the pianist, given a slow intensity by director Neil Bartlett.

Since this review was first published, we have learned that Matt Wand designed the sound effects as the audience walked through the building, but it was actually Tube Uk Ltd and Melvyn Coote who created the sound in the room with the performance. We are pleased to be able to give Tube UK and Melvyn Coote their proper acknowledgement and apologise for omitting them in the first place.

The Pianist, International Festival, Manchester

Published: 08 July 2007

The Independent on Sunday

Chopin's music has defeated Hitler. Against all the odds, the composer's softly rippling Nocturne in D Flat Major radiates a serenity which seems to rise above even the Holocaust and the ruins of Warsaw– the devastation described by Wladyslaw Szpilman's Second World War memoirs in The Pianist.

Director Neil Bartlett's adaptation of this celebrated Jewish musician's astonishing tale of survival is staged with simplicity, as a two-man chamber piece. At the same time, this premiere is a modestly experimental meeting of words and music, half-monologue and half-concert (presented by the pioneering new Manchester International Festival).

In a dark, timber-framed attic, a grand piano stands, caught in a shaft of light. Out of the shadows step the craggy-faced actor Peter Guinness and the renowned pianist Mikhail Rudy. Both are dressed in black suits, like different incarnations of the same man. Walking quietly around the instrument, Guinness speaks to us as Szpilman, describing how he repeatedly escaped death – fleeing the trucks bound for Treblinka where the rest of his family perished, then, almost starving, hiding in an attic, secretly fed in the last days of the war by a merciful German officer.

Intercut with that story, Rudy plays glimmering passages from Chopin's Nocturnes and Preludes and two of Szpilman's own fluid, if less transcendent compositions.

Bartlett's staging does have its disappointments. The attic used for this found-space production is actually in a swish renovated warehouse. The softly-spoken Guinness is sometimes just too calm and, from where I was sitting, Rudy's fortissimos sounded surprisingly thumping at first. Szpilman's text (co-edited by Rudy, who initiated this project) has also been pared down at points with insufficient dexterity. Roman Polanski's film is more grippingly structured and harrowing.

But Szpilman's direct experience of the invasion cannot but make you weep. There are, moreover, some fascinating details here, such as Szpilman's method for stopping himself from going mad with grief: every day he mentally ran through every English book he could remember and each bar of music that he knew.

When Rudy plays Chopin's Nocturne No 20 in C sharp minor – which Szpilman played to the German officer to prove he was a pianist – it is as if a window has been opened, revealing a beautiful world beyond the destruction

.

From The Times

June 20, 2009

The Pianist at the Royal Exchange, Manchester: theatre review

Benedict Nightingale

* * * * *

Surely it’s salutory to be reminded that, compared with the sufferings of other people in other countries in the relatively recent past, our current woes are about as terrible as Eeyore’s burst balloon. Certainly, it’s impossible to emerge from Neil Bartlett’s production of The Pianist, which transforms Wladyslaw Szpilman’s memories of life, half-life and death in the Warsaw Ghetto into a monologue with music, without feeling that most of us know little or nothing about atrocity, loss, danger, endurance, resilience and survival.

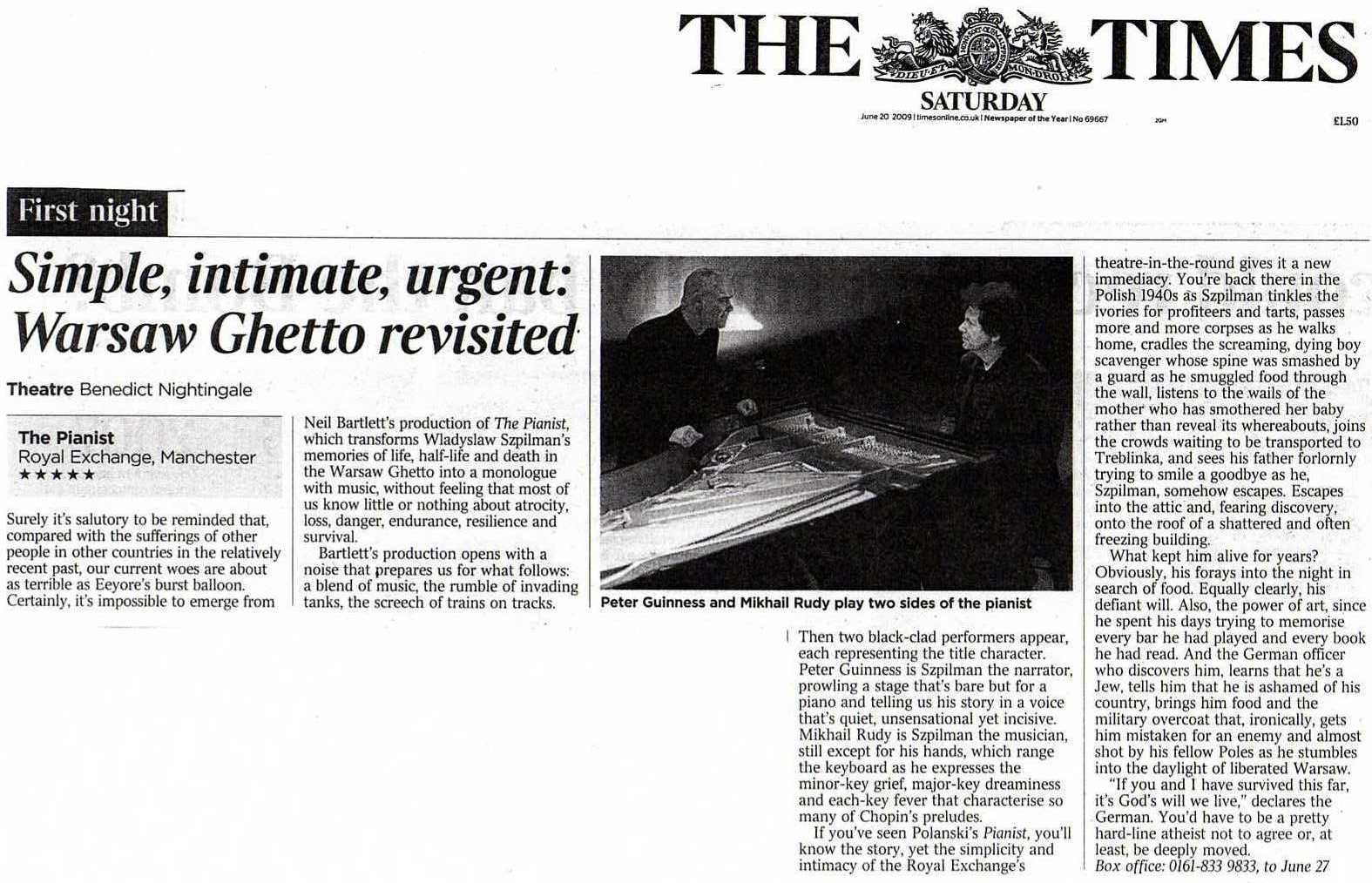

Bartlett’s production opens with a noise that prepares us for what follows: a blend of music, the rumble of invading tanks, the screech of trains on tracks. Then two black-clad performers appear, each representing the title character. Peter Guinness is Szpilman the narrator, prowling a stage that’s bare but for a piano and telling us his story in a voice that’s quiet, unsensational yet incisive. Mikhail Rudy is Szpilman the musician, still except for his hands, which range the keyboard as he expresses the minor-key grief, major-key dreaminess and each-key fever that characterise so many of Chopin’s preludes.

If you’ve seen Polanski’s Pianist, you’ll know the story, yet the simplicity and intimacy of the Royal Exchange’s theatre-in-the-round gives it a new immediacy. You’re back there in the Polish 1940s as Szpilman tinkles the ivories for profiteers and tarts, passes more and more corpses as he walks home, cradles the screaming, dying boy scavenger whose spine was smashed by a guard as he smuggled food through the wall, listens to the wails of the mother who has smothered her baby rather than reveal its whereabouts, joins the crowds waiting to be transported to Treblinka, and sees his father forlornly trying to smile a goodbye as he, Szpilman, somehow escapes. Escapes into the attic and, fearing discovery, on to the roof of a shattered and often freezing building.

What kept him alive for years? Obviously, his forays into the night in search of food. Equally clearly, his defiant will. Also, the power of art, since he spent his days trying to memorise every bar he had played and every book he had read. And the German officer who discovers him, learns that he’s a Jew, tells him that he is ashamed of his country, brings him food and the military overcoat that, ironically, gets him mistaken for an enemy and almost shot by his fellow Poles as he stumbles into the daylight of liberated Warsaw.

“If you and I have survived this far, it’s God’s will we live,” declares the German. You’d have to be a pretty hard-line atheist not to agree or, at least, be deeply moved.

THE SUNDAY TIMES

Songs in the key of life

JASPER REES

The story of Wladyslaw Szpilman, a Jewish pianist who, through blind luck and animal instinct, evaded death in wartime Warsaw, reached a world-wide audience in a film by Roman Polanski. Having experienced the Cracow ghetto, Polanski had impeccable qualifications, and The Pianist won a deserved cargo of Academy Awards in 2003. But there was one element of Szpilman’s narrative the film could not convey: the role played by music in his survival. That omission is redressed in a theatrical version of his memoir that, unusually for a play, features a live performance by a leading classical musician.

The eminent Russian pianist Mikhail Rudy read Szpilman’s memoir when it was first published in France in 2001. The following year, he attempted an experimental staging for the Festival les Estivales de Perpignan, with an actor speaking the words disgorged by Szpilman. “It was not just a reading with musical illustration,” Rudy says. “Music was in this project before the word, rather than the other way round.”

The Pianist was performed for four months in Paris in 2005, and toured through 45 cities last year. For its first incarnation in English, at this year’s Manchester International Festival, Rudy has reshaped the piece with the director Neil Bartlett. In a conscious echo of the half-bombed loft in which Szpilman secreted himself, Bartlett has found a disused attic in the Museum of Science and Industry, where the piece will be performed for a fortnight by Rudy and the actor Peter Guinness.

Music is integral to Szpilman’s odyssey. When half a million Jews were penned into the Warsaw ghetto, the cafe pianist became the breadwinner for his family. Much later, after a Jewish policeman yanked him out of the line for the Auschwitz-bound cattle trucks, with the ghetto destroyed and his safe house discovered, Szpilman staved off madness by playing from memory in his head.

The music Rudy has chosen to soundtrack this infernal journey is by Chopin. It was the Nocturne in C sharp minor that Szpilman was playing on Polish radio when the Germans bombed the power station, and played on the radio again The Pianist, Museum of Science and Industry, Manchester, until July 15 when broadcasting resumed at the end of the war. The Nocturne tumbled out of his unpractised fingers when, in 1944, a humane Wehr-macht officer found him in his garret and requested validation of his claim to be a pianist. There is also a gut-wrenching redeployment of the cloying Raindrop Prelude.

“I tried to find the places in the book where music can tell the same story,” Rudy says. “In the book, there is a story about a great Jewish pedagogue who volunteers to go with his children to the gas chamber, reassuring them that everything will be all right. It’s utter heroism. The Raindrop Prelude is normally associated with sentiment, but when you see the narration, it gives it a totally different meaning. It’s about the impossibility of happiness.”

Bartlett was a reluctant recruit. “Entertainments that take the Holocaust as their subject matter make me instinctively nervous. I’m always so scared they’re going to be sensationalist.” An impromptu concert in Rudy’s Parisian basement won him round. “Working with him has made me feel I’ve never really listened to Chopin’s music before,” says Bartlett, who has not seen Polanski’s film. “It’s stripping this story down to that primary moment when words fail and music begins.”

Rudy’s involvement springs from a personal identification with Szpilman’s story. “What struck me was how much time he spent in total isolation, but living an intense internal life in which his music was continuously present – this similar experience, on a completely different scale.” Rudy’s grandparents were victims of Stalin, while a peripatetic childhood involved nocturnal flits to evade the secret police. He sought political asylum in France in 1977. The Soviet government demanded his extradition, so for six months he was hidden by the French police and taken to a house to continue clandestine nighttime piano practice.

“It’s a play about someone who is totally lost,” Rudy says. “He was not a heroic man. He just survived.”

The Pianist, Museum of Science and Industry, Manchester, until July 15

The Sunday Times July 1, 2007

Outside, the thunder of trains rumbled. Inside, a grand piano awaited its pianist.

Out of the shadows came Rudy, the pianist, and the narrator, Peter Guinness, who between them would share Szpilman’s experiences of suffering and survival.

The production started and finished with the same composition by Chopin. In-between came the haunting words of Wladyslaw, read with great care and conviction by Guinness. Where the words ended, music followed, filling the air with sadness, but also with a means by which to escape from the horror that was unfolding.

Although this was very much Szpilman’s story, you could not help but feel the sorrow that was escaping from the pianist before you. Like Szpilman, Rudy had taken much comfort from his piano during his darkest days as a child moving from one place to another in order to survive.

But in this meeting of music and memoir, Rudy created a powerful performance that portrays the strength of survival that is found in amongst the depths of despair. Shocking and beautiful, this was a stunning production.

uktheatre.net

The Pianist at Manchester Royal Exchange

Published by: Caroline May on 19th Jun 2009 | View all blogs by Caroline May

Two years ago audiences were raving about Neil Bartlett’s Manchester International Festival production of The Pianist, which was originally staged in the highly unconventional setting of a loft above the Museum of Science and Industry. Now there’s another chance to see it with the original cast in the Royal Exchange main house.

The piece is based on the wartime memoirs of Wladyslaw Szpilman, a concert pianist who survived the horrors of Warsaw during World War II – Roman Polanski’s Oscar-winning film from 2003 was based on the same material.

This version of the story opens with Warsaw’s Jewish population already incarcerated in the ghetto - overcrowded, starving, infested with vermin and lice, when typhus inevitably breaks out there is nowhere to bury the dead, and rotting bodies lie stripped naked on the streets. Wladyslaw is now reduced to playing the piano in bars, but eventually his family is summoned for transportation from the ghetto to some unknown destination far away. As the disinfected cattle trucks draw into the station Wladyslaw seizes his chance to flee, and then spends lonely years hiding in the ruins of what had recently been one of Europe’s wealthiest cities, trying to elude starvation, cold and the Nazis.

The auditorium is stark – merely a wooden floor, a grand piano, a chair, and two performers: actor Peter Guinness, who narrates, and pianist Mikhail Rudy, who punctuates the narrative with music by Chopin and Szpilman himself. Peter Guinness, with a piercing gaze that takes in the whole audience from the front stalls to the back of the gods, prowls endlessly around the piano as he repeats his tale with the simplicity of a Greek messenger. It’s an incredibly stripped-down form of story-telling, and the few moments of drama are all the more effective for their rarity. At the keyboard Mikhail Rudy does far more than provide a pretty background accompaniment – sometimes his playing pushes the difficult emotions even further, sometimes music is the only thing which can resolve and diffuse the tension. The frisson when Guinness and Rudy interact is thrilling.

Despite the ostensible minimalism of the design and staging, Chris Davey’s wonderful lighting creates a tangible sense of atmosphere, location, season and mood.

The Royal Exchange main house has never felt so intimate, and The Pianist reveals that it’s not just a wonderful theatre space but also a brilliant venue for chamber music.

CityLife

By Alan Hulme

BASED on the real-life wartime memoirs of Polish pianist Wladyslaw Szpilman - he was playing live on Polish radio when the German bombs began to drop - this heart-rending, Manchester International Festival premiere, is a pretty riveting 90-minute experience.

There was a film, by Roman Polanski, but the inspiration for the current production comes from internationally-acclaimed concert pianist Mikhail Rudy, who not only persuaded award-winning British theatre director Neil Bartlett to take charge, but is also seated here at the Steinway to play the Chopin Preludes and Nocturnes that punctuate the text.

Rudy's reputation alone would be reason enough to buy your ticket, but there's much more…

The play chronicles Szpilman's struggle to stay alive, from 1939, when the Nazis first arrived, to the final days of the German occupation.

As the Nazis take hold, Szpilman and his family are forced into the ghetto, along with the rest of Warsaw's Jewish community. A chance escape later separates them and, as the rest of the ghetto is herded onto trains for the concentration camps, Szpilman becomes a fugitive, living in terror and isolation in the deserted, ruined city, evading capture and struggling to stay alive.

The setting here, at the museum, is part of the experience, as the audience is led to a smoke-wreathed loft. In this gorgeous brick-walled, wooden-ceilinged space, the spectators surround an arena dominated by the piano.

Focused

Deceptively simple lighting pin points the action, which is brilliantly focused and paced by Bartlett. It is all exquisitely done.

With Rudy at the piano, mesmerisingly supplying the pianistic side of Szpilman, actor Peter Guinness (a face you will recognise from works as diverse as Alien III and Casualty) delivers the words quite brilliantly. There are no histrionics as the truly appalling tale unfolds and it is all the more shocking for it.

There are some reservations. It is another holocaust tale and though, of course, holocaust tales must be told over and over, for ever and ever, I didn't find anything I didn't already know in this one.

And there are occasions where the format - of text followed by illustrative Chopin - becomes a tad routine and where the music is asked to carry a weight of horror that it can't sustain.

But overall, this is a five-star experience and I will most certainly remember it as a highlight of this extraordinary festival.

The Pianist is on at the Museum of Science and Industry until Sunday, July 15. Further performances, July 6 - 8 and 10 - 15, all at 8.30 pm. No performances July 4/5.

Reviewed: Wed, 04 July, 2007

Lyn Gardner

The Guardian, Monday 22 June 2009

The Pianist

. Royal Exchange,Manchester

. M2 7DH

. Directed by Neil Bartlett

. Until 27 June

. Box office:

0161-833 9833

.

A tale of terrible loss and enormous courage ... Peter Guiness and Mikhail Rudy in The Pianist

Plucked as if by fate from the cattle truck train that took the rest of his family to the oblivion of the concentration camps, pianist Wladyslaw Szpilman's extraordinary memoir of survival in the ruins of Warsaw for the rest of the war was made into the Oscar-winning movie by Roman Polanski.

This staged version, first seen at the Manchester international festival two years ago, combines horror and beauty to considerable effect by the simple device of pitting Peter Guinness's first-person narration against Mikhail Rudy's piano interludes so that the two appear engaged in a constant conversation of restraint and emotion. Chopin wafts around the theatre like an exquisite reproach to the Nazis. Szpilman was halfway through playing Chopin's Nocturne in C sharp minor when the German army marched into Warsaw; five years later, the same piece saves his skin when he is discovered by a German officer

.

.Only a heart of stone would be unmoved by Szpilman's tale of terrible loss and enormous courage. But the power is all in the direct simplicity of Szpilman's testimony rather than in Neil Bartlett's staging. Last time round, the piece was performed in the attic of a 19th-century warehouse, and by all accounts benefitted enormously from the natural atmosphere. For all the added smoky lighting, the Royal Exchange auditorium is a far more unforgiving space, which lays bare the narrative jerkiness of the edited text and the unanswered questions it raises about exactly how Szpilman survived alone and in constant danger. Watching it in a theatre seems oddly cosy, making you feel a bit like one of the rich Jews in the ghetto cafe where Szpilman once played, who continued to party even while others there were dying of starvation.

FRANKFURTER RUNDSCHAU &Mac221; KULTUR &Mac221; MUSIK

Der Himmel über Warschau

Die Ausstellung „Musik im okkupierten Polen“ lässt ihre Besucher das Leben des von Roman Polanski verfilmten "Pianisten" in pianobegleiteter Sprache erleben.

Den Film kennen viele. Roman Polanskis „Der Pianist“ von 2002 ist, nicht nur wegen des brillanten Hauptdarstellers Adrien Brody, ein bedeutendes Kunstwerk. Es ist ein Film, der zu Tränen rührt und zugleich als historisches Dokument figuriert; ein Film, der das Einzelschicksal schildert und doch kontextuell das große Ganze umschreibt.

Jetzt, an diesem Abend im Kieler Schloss, wird die Erinnerung daran wieder wach. Mit dem Unterschied, dass die Bilder nicht auf einer Leinwand zu sehen sind, sondern durch den Text entstehen, aus ihm heraus wachsen und immer größer, bedrohlicher, aber auch schöner werden. Der Schauspieler Ulrich Matthes liest aus Wladyslaw Szpilmans 1998 erschienenem Lebensbericht „Der Pianist“; Polanskis Film basiert darauf. Er erzählt uns die wundersame Geschichte des polnisch-jüdischen Pianisten und Komponisten, der nach dem Überfall Hitlers auf Polen im Warschauer Ghetto vegetierte, der miterleben musste, wie seine Familie 1942 vom „Umschlagplatz“ ins todbringende Treblinka deportiert und er selbst dabei im letzten Moment gerettet wurde, danach drei Jahre lang ein bejammernswertes Dasein fristete und unter anderem auch nur deswegen überlebte, weil er sich ein anderes Leben hinzu phantasierte.

Matthes gelingt hier etwas Außerordentliches. Er bleibt in seiner Empathie distanziert und nobel, aber er ist demjenigen, in dessen Rolle er für die neunzig (vom Pianisten Mikhail Rudy empfindsam begleiteten) Minuten hinein kriecht, in jedem Satz stets auch ganz nahe. Man weiß, es ist nicht Szpilman, der auf der Bühne sitzt. Und doch glaubt man, es sei seine Stimme, sein Körper, sein Schicksal, das hier geschildert wird. Ein irritierend intensiver Abend.

Nach dem 1. September 1939 brach das rege polnische Musikleben zusammen

Der auch auf eine posthume Ungerechtigkeit hinweist. Wladyslaw Szpilman ist vielen ein Begriff. Aber wer kennt Andrzej Krauthammer? Auch er war ein begnadeter Pianist und Komponist, auch er war Jude, und auch ihm gelang es (unter dem Pseudonym Czajkowski), den Krieg zu überstehen, unter falschem Namen, in wechselnden Verstecken.

In der durch den Musikverleger Frank Harders-Wuthenow initiierten und von Katarzyna Naliwajek kuratierten Ausstellung „Musik im okkupierten Polen“, die im Rahmen des Schleswig-Holstein-Festivals gegenwärtig im Kieler Schloss zu sehen ist und im November nach Berlin kommt, begegnet uns Krauthammer wieder, und ebenso eine große Zahl von Künstlern, die bis 1939 das pralle Musikleben Polens prägten und sich nach dem 1. September der Tatenlosigkeit, der Verfolgung oder beidem ausgesetzt sahen.

Polen, das zeigt die Ausstellung anhand sorgfältig recherchierter Dokumente, wurde nicht nur zwischen Hitler und Stalin aufgeteilt und zerstört. Polen wurde gedemütigt. Anscheinend genügte es den Invasoren nicht, das Land zu verwüsten, es bereitete ihnen Spaß, kulturelle Symbole und damit einen Teil der Musikgeschichte auszulöschen. Besonders den Nationalheiligen Frédéric Chopin traf es schwer. Seine Musik wurde verboten, namhafte Interpreten seiner Musik, wie Halina Kalmanowicz, Leon Borunski, Andrzej Tokarski und Leopold Münzer, wurden ermordet, und das Bronzedenkmal Chopins in Warschau sprengten die Nazis 1940. Die Einzelteile brachte man nach Deutschland, um sie in einer Gießerei zu verflüssigen und militärischen Zwecken zuzuführen.

Chopins Denkmal wurde gesprengt, später wurde er quasi zum Deutschen erklärt

Ebenso auf Nimmerwiedersehen verschwanden Autographe einzelner Kompositionen, Gemälde und Abbildungen Chopins sowie ein wesentlicher Teil seiner schriftlichen Korrespondenz, mithin ein Stück Weltkulturerbe. Doch die Fälschung ging weiter. Hans Frank, der Leiter des so benannten Generalgouvernements Polen, organisierte 1943 in Krakau eine Chopin-Ausstellung, die Leben und Werk dieses Musikers germanisierte.

Gleichviel: Das Musikleben, auch davon berichtet die Ausstellung anschaulich (unter anderem mit einem polnischen Fernsehfilm, der auf Zeugenaussagen von Lagerinsassen in Auschwitz basiert), existierte weiter, trotzig. Witold Lutoslawski trat mit Andrzej Panufnik als Klavierduo in Cafés auf, im Warschauer Ghetto scherten sich die Musiker nicht einmal um das Verdikt, keine arische Musik aufführen zu dürfen, und selbst in den Vernichtungslagern spielte die Musik eine Rolle, wie man sie heute kaum mehr imaginieren kann. Musik war Ausdruck von Hoffnung ebenso wie von Widerstandsgeist, Musik war manchmal sogar bestimmender Teil des Alltags.

Und sie konnte Leben verlängern. Wie im Fall von Leopold Kozowski, der überlebte, weil er dem Kommandanten des Zwangsarbeiterlagers Jaktorów den Walzer „An der schönen blauen Donau“ auf dem Akkordeon beibrachte. Oder wie bei Wladyslaw Szpilman: Als der Nazi-Offizier Hosengeld den Verwahrlosten auf dem Dachboden eines Hauses entdeckte, fragte er ihn nach seinem Beruf. Szpilman antwortete pflichtgemäß, er sei Pianist. Hosenfeld forderte ihn auf, etwas vorzuspielen. Szpilman intonierte mit zitternden Fingern das cis-Moll-Nocturne von Chopin und erhielt als Dank Brot und Marmelade. Und der Himmel über Warschau weinte Schneeflocken.

Kieler Schloss: bis 29. August. www.shmf.de

|

|

|

|

|

|